Our Health Library information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Please be advised that this information is made available to assist our patients to learn more about their health. Our providers may not see and/or treat all topics found herein.

Topic Contents

- Overview

- Caregiver Burden

- Coping Strategies and Self-Efficacy

- Assessment of Caregivers (Screening or Evaluation)

- The Needs of Caregivers During Specific Phases of the Cancer Trajectory

- Interventions to Prevent, Reduce, or Ameliorate Caregiver Burden

- Interventions for Caregivers During Specific Phases of the Cancer Trajectory

- Parents as Caregivers

- Latest Updates to This Summary (03 / 12 / 2024)

- About This PDQ Summary

Informal Caregivers in Cancer: Roles, Burden, and Support (PDQ®): Supportive care - Health Professional Information [NCI]

This information is produced and provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The information in this topic may have changed since it was written. For the most current information, contact the National Cancer Institute via the Internet web site at http://cancer.gov or call 1-800-4-CANCER.

Overview

Informal caregiving is broadly defined as services provided by an unpaid person, such as helping with personal needs and household chores, managing a person's finances, arranging for outside services, or visiting regularly.[1,2] An informal caregiver is usually a relative or friend who may or may not live in the same household as the person with cancer who requires care.

Informal caregiving provides significant practical and economic benefits. This summary describes the experiences of informal caregivers of individuals with cancer, enumerates the risk factors for caregiver burden (which is often associated with negative psychological consequences), and evaluates evidence-based interventions designed to reduce the burden of informal caregiving. The goal of the summary is to provide the oncology clinician with both a deeper appreciation of the importance of informal caregivers, and the information necessary to recognize burdened caregivers and effectively intervene.

Who Are Informal Caregivers and What Roles Do They Play?

In 2016, the National Alliance for Caregiving reported an analysis of the survey responses of 111 caregivers who self-identified as providing care to a person with cancer.[3] The respondents were part of a much larger study that identified a representative sample of adult caregivers who provided unpaid care to an adult relative or friend in the 12 months preceding the time of the survey.

The following findings provide a snapshot of informal caregivers of people with cancer and the challenges they face:

- 58% were women.

- 88% cared for a relative.

- 39% lived with the person being cared for.

- 50% reported high emotional stress related to caregiving.

- 25% reported high financial strain.

- 50% were employed while caregiving, working an average of 35 hours per week.

- 73% were involved in discussions about care during hospitalization; however, only about half of these (54%) were asked what help was needed after discharge.

- 72% assisted with medical tasks.

- 43% reported needing help to manage emotional and physical stress.

- 40% wanted help making end-of-life decisions.

- 33% wanted help keeping their friend or relative safe at home.

- Caregiving for patients with cancer was noted to be episodic and lasted for approximately 2 years on average.

Caregiving is also relational.[4,5] In addition, there are important implications for the interconnectedness between patient and caregiver that the oncology clinician should be aware of, including the following:

- Patients and caregivers influence each other's mental and physical health (partner effects) in addition to their own outcomes (actor effects).[6]

- The psychological well-being of caregivers seems to influence patients' evaluations of the quality of their care. One survey of 689 patients and their caregivers demonstrated that higher levels of depression in caregivers were associated with patients' ratings of lower quality of care.[7]

- There are important distinctions between the experiences of patients and informal caregivers. A semistructured interview study of 23 patients with advanced colorectal cancer and 23 caregivers demonstrated the prevalence and nature of these differences.[8] Participants agreed on four challenges:

- Emotionally processing the initial diagnosis or recurrence.

- Managing the practical and emotional aspects of patient care.

- Facing an uncertain future.

- Encountering symptom-related suffering.

In no instance, however, did patient and caregiver identify the same key challenge. Clinicians are thus advised to assess caregiver needs independent of patient needs.

- The caregiver may not be an accurate informant of the patient's experience. One study demonstrated that caregivers correctly reported 67% of patients' physical difficulties, 69% of patients' psychological difficulties, and 40% of patients' social difficulties.[9] There were no predictive demographic factors. In further support of the need for caution, an analysis of office visits recorded on audiotape revealed that caregivers often spoke on behalf of patients without validation by the patients.[10] In addition to this pseudo-surrogacy, caregivers often conflated their concerns with those of the patients.

The Psychological Consequences of Caregiving

The psychological consequences of caregiving vary widely. Some caregivers report positive outcomes such as post-traumatic growth/benefit finding. But a minority of caregivers experience anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The following paragraphs summarize the salient literature.

Benefit finding: Results of several qualitative studies (interviews or narrative questionnaires) of caregivers of either adult cancer survivors [11,12] or childhood cancer survivors [13,14] revealed common themes on the positive aspects of caregiving:

- Closer relationships with others, including partners and children.

- Greater appreciation of life.

- Clarification of life priorities.

- Increased faith.

- More empathy for others.

- Better health habits.

These common themes are more quantitatively measured by using the Benefit Finding Scale. Six domains of caregivers' personal growth have been identified [15] and are consistent for both caregivers of survivors and those in bereavement:[16]

- Acceptance.

- Empathy.

- Appreciation.

- Family.

- Positive self-view.

- Reprioritization.

Anxiety and/or depression: Several large survey studies provide more-accurate estimates of the prevalence and potential covariates or risk factors for anxiety and depression; these are summarized below.

- In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 35 studies representing 11,396 caregivers of people with cancer, the pooled prevalence of depressive symptoms was 42.08% (95% confidence interval, 34.71%–49.45%). Studies were included in the meta-analysis if they used validated instruments to assess depression. However, the authors did not differentiate between studies that used cutoff scores associated with mild depressive symptoms and clinically significant depression.[17][Level of evidence: II]

- A telephone survey of 196 caregivers of patients with renal cell carcinoma studied the associations between psychological adjustment and caregivers' experiences and unmet needs. Investigators demonstrated that 64% of caregivers had at least one significant unmet need; 53% had three or more unmet needs; and 29% had ten or more unmet needs.[18] Investigators found elevated anxiety in 29% of respondents and depression in 11%. Unmet information needs and worse experiences of care during surgery were risk factors for caregiver depression. Unmet information needs was the only risk factor for anxiety.

- In a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data on caregivers of patients with advanced-stage lung or colorectal cancers enrolled in a randomized trial of early palliative care,[19] a significant proportion of caregivers reported elevated levels of anxiety (42.2%) or depression (21.5%). Risk factors for caregiver depression were patients' expectation of cure and patients' use of emotional support coping. Patients' use of acceptance coping was associated with less caregiver anxiety. A study of caregivers of patients with pancreatic cancer reported similar results: 39% of caregivers had elevated levels of anxiety, and 14% had elevated levels of depression, compared with community norms.[20]

PTSD: One of the negative consequences of caregiving that persists is PTSD. A preliminary study of caregivers of patients with head and neck cancer 6 months after diagnosis demonstrated that approximately 20% met the criteria for PTSD.[21] Risk factors for PTSD included the following:

- Caregiver perception of low treatment benefit.

- Caregiver perception of many patient symptoms.

- Caregiver use of avoidant coping strategies.

The same investigators also showed in a similar population that differences in illness perceptions were dynamic over 6 months, but greater differences were correlated with reduced health-related quality of life (QOL) in patients.[22]

Decline in caregiver QOL: Several investigators have published measures of caregiver QOL while patients were undergoing active treatment. One study demonstrated that caregivers of patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation experience a decline in their QOL, as measured by the physical and mental component of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36).[5]

Patients receiving palliative therapy also rely heavily on informal caregivers. In a study of 201 informal caregivers of patients undergoing palliative radiation therapy for advanced cancer, additional employment of the caregiver, cohabitation, poor patient performance status, and interest in accessing more support services were significantly correlated with higher caregiver burden (poorer QOL).[23]

In summary, a caregiver provides essential support and resources to the person with cancer. The role of informal caregiver, however, creates demands that may exceed the caregiver's resources and, ultimately, cause negative psychological consequences. The remainder of this summary focuses on the significant minority of caregivers who experience unmet needs and increased physical and psychological distress. After a brief review of the concept of caregiver burden, information about the demands on caregivers, resources valued by caregivers, potential moderators, and coping strategies will be presented.

References:

- Caregiving in the U.S. 2020. Washington, DC: National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020. Available online. Last accessed March 11, 2024.

- Kim Y, Kashy DA, Kaw CK, et al.: Sampling in population-based cancer caregivers research. Qual Life Res 18 (8): 981-9, 2009.

- Cancer Caregiving in the U.S.: An Intense, Episodic, and Challenging Care Experience. Bethesda, Md: National Alliance for Caregiving, 2016. Available online. Last accessed March 11, 2024.

- Litzelman K, Green PA, Yabroff KR: Cancer and quality of life in spousal dyads: spillover in couples with and without cancer-related health problems. Support Care Cancer 24 (2): 763-771, 2016.

- El-Jawahri AR, Traeger LN, Kuzmuk K, et al.: Quality of life and mood of patients and family caregivers during hospitalization for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer 121 (6): 951-9, 2015.

- Kershaw T, Ellis KR, Yoon H, et al.: The Interdependence of Advanced Cancer Patients' and Their Family Caregivers' Mental Health, Physical Health, and Self-Efficacy over Time. Ann Behav Med 49 (6): 901-11, 2015.

- Litzelman K, Kent EE, Mollica M, et al.: How Does Caregiver Well-Being Relate to Perceived Quality of Care in Patients With Cancer? Exploring Associations and Pathways. J Clin Oncol 34 (29): 3554-3561, 2016.

- Mosher CE, Adams RN, Helft PR, et al.: Family caregiving challenges in advanced colorectal cancer: patient and caregiver perspectives. Support Care Cancer 24 (5): 2017-2024, 2016.

- Libert Y, Merckaert I, Slachmuylder JL, et al.: The ability of informal primary caregivers to accurately report cancer patients' difficulties. Psychooncology 22 (12): 2840-7, 2013.

- Mazer BL, Cameron RA, DeLuca JM, et al.: "Speaking-for" and "speaking-as": pseudo-surrogacy in physician-patient-companion medical encounters about advanced cancer. Patient Educ Couns 96 (1): 36-42, 2014.

- Mosher CE, Adams RN, Helft PR, et al.: Positive changes among patients with advanced colorectal cancer and their family caregivers: a qualitative analysis. Psychol Health 32 (1): 94-109, 2017.

- Von Ah D, Spath M, Nielsen A, et al.: The Caregiver's Role Across the Bone Marrow Transplantation Trajectory. Cancer Nurs 39 (1): E12-9, 2016 Jan-Feb.

- Willard VW, Hostetter SA, Hutchinson KC, et al.: Benefit Finding in Maternal Caregivers of Pediatric Cancer Survivors: A Mixed Methods Approach. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 33 (5): 353-60, 2016.

- Hensler MA, Katz ER, Wiener L, et al.: Benefit finding in fathers of childhood cancer survivors: a retrospective pilot study. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 30 (3): 161-8, 2013 May-Jun.

- Kim Y, Schulz R, Carver CS: Benefit-finding in the cancer caregiving experience. Psychosom Med 69 (3): 283-91, 2007.

- Kim Y, Carver CS, Schulz R, et al.: Finding benefit in bereavement among family cancer caregivers. J Palliat Med 16 (9): 1040-7, 2013.

- Bedaso A, Dejenu G, Duko B: Depression among caregivers of cancer patients: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology 31 (11): 1809-1820, 2022.

- Oberoi DV, White V, Jefford M, et al.: Caregivers' information needs and their 'experiences of care' during treatment are associated with elevated anxiety and depression: a cross-sectional study of the caregivers of renal cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 24 (10): 4177-86, 2016.

- Nipp RD, El-Jawahri A, Fishbein JN, et al.: Factors associated with depression and anxiety symptoms in family caregivers of patients with incurable cancer. Ann Oncol 27 (8): 1607-12, 2016.

- Janda M, Neale RE, Klein K, et al.: Anxiety, depression and quality of life in people with pancreatic cancer and their carers. Pancreatology 17 (2): 321-327, 2017 Mar - Apr.

- Richardson AE, Morton RP, Broadbent EA: Illness perceptions and coping predict post-traumatic stress in caregivers of patients with head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer 24 (10): 4443-50, 2016.

- Richardson AE, Morton RP, Broadbent EA: Changes over time in head and neck cancer patients' and caregivers' illness perceptions and relationships with quality of life. Psychol Health 31 (10): 1203-19, 2016.

- Duimering A, Turner J, Chu K, et al.: Informal caregiver quality of life in a palliative oncology population. Support Care Cancer 28 (4): 1695-1702, 2020.

Caregiver Burden

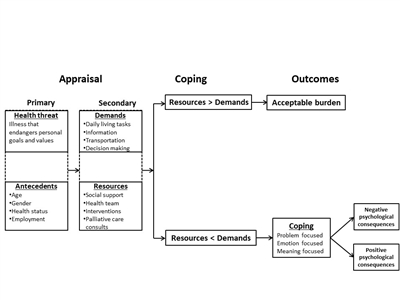

The term caregiver burden describes a caregiver's perceptions of the demands of caregiving and the resources available for addressing those demands. The Transactional Model of Stress and Coping is a useful framework for describing the relationships among caregiver demands, resources, burden, and the psychological consequences of being burdened.[1] From this perspective, a burden is perceived when the demands on the caregiver exceed the resources available to him or her. See the figure below for an illustration of how this framework may be applied to caregiver burden.

The process begins with the primary appraisal, which is a judgment about the relevance of the health threat and any demands on the caregiver. A demand that is judged to be relevant receives a secondary appraisal to evaluate the likelihood that available resources have the potential to reduce or overcome the demand. Burden is perceived to be high when the difficulty of the demand outweighs the available resources. Coping strategies may also determine whether the psychological consequences of the perceived burden are negative or positive.

The Transactional Model of Stress and Coping may explain why some caregivers experience burden and negative psychological consequences. Clinicians may intervene to reduce demands, increase resources, or foster adoptive coping. The text for antecedents, demands, and resources is from examples in the text of this summary.

The Transactional Model of Stress and Coping shown above has not been validated and serves to organize the remainder of the summary.

Primary Appraisal: Demands on Informal Caregivers

Qualitative analysis of interviews: A mixed-methods study of 48 informal caregivers of patients undergoing chemotherapy demonstrated several notable findings.[2] First, 68% of the caregivers had one or no unmet needs; on the other hand, a minority (23%) had five to ten unmet needs. Second, the most common needs were for information about the risks and potential benefits of chemotherapy (79%) and managing side effects at home (78%). Other information-related needs included information about self-care, complementary and alternative therapies, and local community-based resources.

One group of investigators interviewed six patients with head and neck cancer and their spouses within 6 months of completing treatment. Thematic analysis demonstrated several unmet needs, including the following:[3]

- Better preparation for side effects.

- Clearer timeline of recovery.

- Strategies to deal with the emotions experienced by patients and spouses during treatment.

The complexity of a caregiver's life is further highlighted in a systematic review of qualitative studies of informal caregivers of patients with cancer and symptoms or signs of cachexia.[4] The following themes were identified:

- Impact on everyday life.

- Attempts of caregiver to take charge.

- Need for health care provider input.

- Conflict with patient.

- Negative emotions.

Surveys: To provide a more-accurate assessment of the needs of caregivers, one group of investigators developed and demonstrated the psychometric validity of the Supportive Care Needs Survey—Partners and Caregivers (SCNS–P&C).[5] More than 500 caregivers of patients enrolled in a cancer survivor study returned surveys for analysis. The mean age of caregivers was 60.6 years (range, 16–85 years).

The diagnoses of survivors included the following:

- Prostate cancer (32%).

- Blood cancers (16.3%).

- Breast cancer (13.2%).

- Melanoma (11.5%).

- Colorectal cancer (11.3%).

- Head and neck cancer (8.6%).

- Lung cancer (7.1%).

Analysis revealed four domains of needs:

- Health care service.

- Psychological and emotional.

- Work and social.

- Information.

Investigators using the SCNS–P&C to conduct a telephone survey of 196 caregivers of patients with renal cell carcinoma demonstrated that 64% of caregivers had at least one significant unmet need; 53% had three or more unmet needs; and 29% had ten or more unmet needs.[6] For each domain of needs, the proportion of respondents reporting a moderate or high unmet need was as follows:

- Health care service, 30%.

- Psychological and emotional, 30%.

- Work and social, 23%.

- Informational, 18%.

In another study, 188 patient-caregiver dyads completed the SCNS–P&C.[7] The caregivers were predominantly female; the average age was 57.8 years. Caregivers reported higher levels of distress and anxiety than did patients. A minority (14%) reported no unmet needs, and a plurality (44%) reported ten or more unmet needs. The principal unmet caregiver needs were as follows:

- Support in managing fears about the patient's condition.

- Receiving disease-related information.

- Receiving emotional support for themselves.

There were no strong predictors of caregiver needs; however, unmet patient needs and caregiver anxiety were modestly associated with unmet needs in caregivers.

Similarly, the SCNS–P&C was administered to 166 lung cancer patient–caregiver dyads in Taiwan.[8] The top unmet needs were information needs.

Caregiver tasks: A cross-sectional study demonstrated that participation in assisting patients in activities of daily living (ADLs) increased caregiver burden.[9] This study enrolled 100 caregivers of older adults (age >65 years) with cancer. The caregivers were mostly women, married to and living with the patients. Employment status and participation in ADLs were risk factors for increased burden on multivariate analysis. Similarly, a survey of 590 caregivers demonstrated that primary caregivers assumed a significant workload.[10] As a consequence, they experienced challenges in maintaining employment and social relations, and had financial difficulties. On the other hand, primary caregivers experienced the most personal growth through the experiences. A subsequent systematic review supported the results of the two studies.[11] A more nuance view is that the perceived burden and the psychological consequences may relate to the sense of mastery for any given caregiver task.[12]

Secondary Appraisal: Resources for Informal Caregivers

The following list captures the resources that caregivers identified in multiple studies as important:

- Recognition by health care providers of the informal caregivers' roles, responsibilities, and challenges.

- Information about treatment plans, goals, anticipated complications or side effects, and likely outcomes.

- Guidance for how to respond to changes in patients' physical and emotional health over the disease trajectory.

- Support in coping with the stress of their role (for which they are most often unprepared and untrained).

- Detailed education about medical and nursing tasks they are expected to perform, such as giving injections, providing wound care, and managing side effects.

Potential Moderators of Caregiver Burden

Factors associated with increased caregiver burden include the following:

- Female gender.

- Age (younger or older with impaired health status).

- Race and ethnicity.

- Lower socioeconomic status.

- Employment status.

- Role strain.

- Site of care.

- Patient characteristics (e.g., level of anxiety, depression, functional status, and quality of life [QOL]).[13][Level of evidence: II]

Female gender

Female gender is an established risk factor for increased burden.[14,15][Level of evidence: II] A survey of 308 self-identified caregivers of patients with advanced cancer sought to characterize potential determinants of the increased burden for female caregivers.[16] Results demonstrated that hope and perceived fulfillment of support needs were the most significant protective factors against burden for both genders. Women who were employed or who used emotion-focused coping were more likely to perceive burden. Results suggest that interventions to address role strain and alternative coping strategies may be useful.

Age

Family caregivers often feel unprepared, have inadequate knowledge, and receive little guidance from the oncology team for providing care to the cancer patient.[17] Older caregivers are especially vulnerable because they may present with comorbidities, may be living on fixed incomes, and have reduced social support networks. In addition, older caregivers of cancer patients may neglect their own health needs, have less time to exercise, forget to take their own prescription medications, and become fatigued from interrupted sleep. It is therefore common for older caregivers to have poor physical health, depression, and even increased mortality.[18,19]

Younger caregivers must generally juggle work, family responsibilities, and sacrifices involving their social lives. Middle-aged caregivers typically worry about missed workdays, interruptions at work, taking leaves of absence, and reduced productivity.[20,21]

Race and ethnicity

In a meta-analysis of 116 empirical studies, Asian American caregivers were found to provide more caregiving hours than were White, African American, and Hispanic caregivers; to use lower levels of formal support services; and to have fewer financial resources, lower levels of education, and higher levels of depression than did the other subgroups.[22] These findings are important for the oncology team because caregivers with no outside help are more depressed than are those who receive help.

A study involving unmet needs and service barriers among Asian American caregivers found that caregivers refused outside help because they "felt too proud to accept it" or "didn't want outsiders coming in"; other barriers included "bureaucracy too complex" or "can't find qualified providers."[23] A study of hospice use by Asian American patients found that family reluctance to discuss a patient's health status among themselves resulted in lower rates of hospice enrollment. This reluctance was rooted in the belief that talking about death or dying is bad luck, which could complicate discussions about prognosis and informed consent.[24] Keeping a cancer diagnosis secret from a patient and avoiding discussions about disease progression can add to a caregiver's sense of burden and responsibility.

Similarly, Hispanic and African American patients and caregivers underutilize community health resources, including counseling and support groups, home care, residential care, and hospice services. One important reason is that strong family ties may prevent these caregivers from seeking help outside of the family unit.[25] A study that compared African American, White, and Hispanic caregivers found that 75% of Hispanic patients and 60% of African American patients lived with the family of the primary caregiver. The racial and ethnic minority families relied more on informal caregiving from friends and relatives and had larger social support networks than did the White families. However, this increased sense of obligation to provide care for older family members was associated with more caregiving hours, greater resignation about caregiving, higher levels of caregiver strain, and a larger reduction in household income compared with White caregivers.[25,26] For more information, see the Disparities in Hospice Utilization section in Hospice.

Another study analyzed reports of employment loss due to caregiving responsibilities. Results showed that African American and Hispanic caregivers were more likely than White caregivers to reduce their work hours to care for patients. In addition, African American and Hispanic caregivers were reluctant to use formal nursing home services for their loved ones. The decision to reduce work hours rather than place a relative in a nursing home was associated with increased psychological, social, and financial burden.[27]

Socioeconomic status

Substantial out-of-pocket costs involved in caregiving can create financial strain for the families of patients with cancer. Low personal and household incomes and limited financial resources may also place families at risk of treatment noncompliance or making treatment-related decisions on the basis of income.[28]

In a secondary analysis of longitudinal data (at baseline, 4–6 weeks, and 3 months) collected during the Improving Communication in Older Cancer Patients and their Caregivers trial, investigators assessed caregiver burden in 414 caregivers of older patients with advanced cancer.[29][Level of evidence: II] The authors used the Caregiver Reaction Assessment, which includes five subscales measuring domains of caregiving burden: self-esteem, disrupted schedule, financial problems, lack of family support, and health problems. The authors also assessed caregivers' rurality, defining rural residence as living in 2010 Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes other than 1.0, 1.1, 2.0, 2.1, 3.0, 4.1, 5.1, 7.1, 8.1, or 10.1. The authors found that rural residence was significantly associated with more disrupted schedules, financial problems, and lack of social support among caregivers with a high school education or less.

Employment

Informal caregiving is known to impose economic burdens on families. One study analyzed data from 458 cancer survivors who responded to the U.S. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) Experiences with Cancer Survivorship Survey (ECSS) and from 4,706 cancer survivors who responded to the LIVESTRONG 2012 Survey for People Affected by Cancer (SPAC). Results demonstrated that 25% of those responding to the MEPS ECSS and 29% of those responding to the SPAC reported that their caregivers made extended employment changes, including taking paid or unpaid time off and/or making changes in hours, duties, or employment status.[30] The work productivity of 70 caregivers of patients with advanced cancer showed a 23% decline because of missed work.[31] More hours of caregiving were associated with greater loss in productivity, which was associated with higher rates of caregiver depression and anxiety. A study of 89 caregivers of advanced-cancer patients showed that 69% reported some form of adverse impact on work; this increased to 77% during the end-of-life period.[32]

Some research has shown an incremental increase in the economic burden of caregiving, assessed from disease and demographic characteristics. A study of 78 caregivers of women with advanced breast cancer showed that loss of productivity (absenteeism and reduced productivity at work) was greater for caregivers of women with progressive disease than for caregivers of those who were free of disease.[33] A survey of 1,629 caregivers of people with lung and colorectal cancers demonstrated that economic burden was highest for caregivers of individuals with lung cancer or stage 4 disease.[34] A study of 54 caregivers showed that African American and Hispanic caregivers reported greater distress related to employment and finances than did White caregivers.[35] A study of partner caregivers of men with prostate cancer showed that caregivers with lower incomes (<$40,000/year) spent more time on informal caregiving than did those with higher incomes.[36]

The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA) was designed to give employees the option of taking time off from work for their own serious medical condition or that of a relative without losing their jobs or benefits.[37] Family members are entitled to a maximum of 12 weeks' leave under the law.

Role strain

Role strain is experienced when the perceived rights, duties, and behaviors of one socially defined role (e.g., employee) conflict with the rights, duties, and behaviors of a different role (e.g., student). The multiple roles performed by caregivers of cancer patients can compete for caregivers' physical and emotional resources. A study of 457 middle-aged caregivers showed that the more social roles a caregiver performed, the more likely the caregiver was to experience stress and negative affect.[38] In a population-based study of 1,234 adult-child and spousal caregivers of patients with lung or colorectal cancer, caregiver employment was associated with higher social/emotional caregiver burden.[39][Level of evidence: II] It is important to recognize, however, that employed caregivers may benefit from the respite provided by work and from the support of employers and coworkers, which enable them to replenish their psychological resources.[38] Thus, multiple roles do not always engender strain.

Site of care

Cancer care is provided in multiple physical locations that vary in their ability to provide support services for caregivers. Thus, site of care may be considered a risk factor for caregiver burden. This claim is supported by the results of a qualitative interview study of 12 patients and 12 caregivers about the challenges faced in transitioning from hospital to home.[40] The investigators identified four salient themes:

- Ongoing concerns related to disease and its treatment.

- Needing timely help.

- Resuming control and normality.

- Appreciating the care transition.

An independent study of dyads demonstrated that the transition to home is very stressful because of the need to deal with symptoms, and uncertainty about prognosis and disease progression.[41] Therefore, increased caregiver burden caused by transitions in sites of care should be recognized and ameliorated, when possible, with home nursing visits.

Unplanned changes in sites of care, such as hospital readmission, also place increased demands on caregivers. A total of 129 dyads of older adults with cancer and their family caregivers were studied to determine factors for unplanned hospital admissions.[42] Investigators found that severity of symptoms, rather than caregiver knowledge—a target of many interventions—predicted unplanned hospital admissions in older adults with cancer during the active treatment phase. These results suggest that symptom management interventions may reduce stressful events more than does increasing caregiver knowledge about symptoms.

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics may also influence caregiver burden. In a cross-sectional study of 441 older patient-caregiver dyads with advanced cancer, patients with higher levels of anxiety and depression, worse functional status, and poorer QOL were associated with increased reports of caregiver burden, regardless of time spent caregiving.[13][Level of evidence: II]

Similarly, in a cross-sectional study of 172 dyads of patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers, caregivers of patients admitted to an acute palliative care unit reported worse stress burden and mental health than caregivers of patients receiving outpatient supportive care.[43][Level of evidence: II]

References:

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S: Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer Publishing Co, 1984.

- Ream E, Pedersen VH, Oakley C, et al.: Informal carers' experiences and needs when supporting patients through chemotherapy: a mixed method study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 22 (6): 797-806, 2013.

- Badr H, Herbert K, Reckson B, et al.: Unmet needs and relationship challenges of head and neck cancer patients and their spouses. J Psychosoc Oncol 34 (4): 336-46, 2016 Jul-Aug.

- Wheelwright S, Darlington AS, Hopkinson JB, et al.: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of quality of life in the informal carers of cancer patients with cachexia. Palliat Med 30 (2): 149-60, 2016.

- Girgis A, Lambert S, Lecathelinais C: The supportive care needs survey for partners and caregivers of cancer survivors: development and psychometric evaluation. Psychooncology 20 (4): 387-93, 2011.

- Oberoi DV, White V, Jefford M, et al.: Caregivers' information needs and their 'experiences of care' during treatment are associated with elevated anxiety and depression: a cross-sectional study of the caregivers of renal cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 24 (10): 4177-86, 2016.

- Sklenarova H, Krümpelmann A, Haun MW, et al.: When do we need to care about the caregiver? Supportive care needs, anxiety, and depression among informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Cancer 121 (9): 1513-9, 2015.

- Chen SC, Chiou SC, Yu CJ, et al.: The unmet supportive care needs-what advanced lung cancer patients' caregivers need and related factors. Support Care Cancer 24 (7): 2999-3009, 2016.

- Hsu T, Loscalzo M, Ramani R, et al.: Factors associated with high burden in caregivers of older adults with cancer. Cancer 120 (18): 2927-35, 2014.

- Lund L, Ross L, Petersen MA, et al.: Cancer caregiving tasks and consequences and their associations with caregiver status and the caregiver's relationship to the patient: a survey. BMC Cancer 14: 541, 2014.

- Ge L, Mordiffi SZ: Factors Associated With Higher Caregiver Burden Among Family Caregivers of Elderly Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Cancer Nurs 40 (6): 471-478, 2017 Nov/Dec.

- Stetz KM: Caregiving demands during advanced cancer. The spouse's needs. Cancer Nurs 10 (5): 260-8, 1987.

- Semere W, Althouse AD, Rosland AM, et al.: Poor patient health is associated with higher caregiver burden for older adults with advanced cancer. J Geriatr Oncol 12 (5): 771-778, 2021.

- Kim Y, van Ryn M, Jensen RE, et al.: Effects of gender and depressive symptoms on quality of life among colorectal and lung cancer patients and their family caregivers. Psychooncology 24 (1): 95-105, 2015.

- Decadt I, Laenen A, Celus J, et al.: Caregiver distress and quality of life in primary caregivers of oncology patients in active treatment and follow-up. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 30 (3): e13399, 2021.

- Schrank B, Ebert-Vogel A, Amering M, et al.: Gender differences in caregiver burden and its determinants in family members of terminally ill cancer patients. Psychooncology 25 (7): 808-14, 2016.

- Scherbring M: Effect of caregiver perception of preparedness on burden in an oncology population. Oncol Nurs Forum 29 (6): E70-6, 2002.

- Given CW, Stommel M, Given B, et al.: The influence of cancer patients' symptoms and functional states on patients' depression and family caregivers' reaction and depression. Health Psychol 12 (4): 277-85, 1993.

- Schulz R, Beach SR: Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. JAMA 282 (23): 2215-9, 1999.

- Cameron JI, Franche RL, Cheung AM, et al.: Lifestyle interference and emotional distress in family caregivers of advanced cancer patients. Cancer 94 (2): 521-7, 2002.

- Given B, Sherwood PR: Family care for the older person with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs 22 (1): 43-50, 2006.

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S: Ethnic differences in stressors, resources, and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: a meta-analysis. Gerontologist 45 (1): 90-106, 2005.

- Li H: Barriers to and unmet needs for supportive services: experiences of Asian-American caregivers. J Cross Cult Gerontol 19 (3): 241-60, 2004.

- Ngo-Metzger Q, McCarthy EP, Burns RB, et al.: Older Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders dying of cancer use hospice less frequently than older white patients. Am J Med 115 (1): 47-53, 2003.

- Guarnaccia PJ, Parra P: Ethnicity, social status, and families' experiences of caring for a mentally ill family member. Community Ment Health J 32 (3): 243-60, 1996.

- Cox C, Monk A: Strain among caregivers: comparing the experiences of African American and Hispanic caregivers of Alzheimer's relatives. Int J Aging Hum Dev 43 (2): 93-105, 1996.

- Covinsky KE, Eng C, Lui LY, et al.: Reduced employment in caregivers of frail elders: impact of ethnicity, patient clinical characteristics, and caregiver characteristics. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56 (11): M707-13, 2001.

- Hayman JA, Langa KM, Kabeto MU, et al.: Estimating the cost of informal caregiving for elderly patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 19 (13): 3219-25, 2001.

- Xu H, Kadambi S, Mohile SG, et al.: Caregiving burden of informal caregivers of older adults with advanced cancer: The effects of rurality and education. J Geriatr Oncol 12 (7): 1015-1021, 2021.

- de Moor JS, Dowling EC, Ekwueme DU, et al.: Employment implications of informal cancer caregiving. J Cancer Surviv 11 (1): 48-57, 2017.

- Mazanec SR, Daly BJ, Douglas SL, et al.: Work productivity and health of informal caregivers of persons with advanced cancer. Res Nurs Health 34 (6): 483-95, 2011.

- Grunfeld E, Coyle D, Whelan T, et al.: Family caregiver burden: results of a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients and their principal caregivers. CMAJ 170 (12): 1795-801, 2004.

- Lambert-Obry V, Gouault-Laliberté A, Castonguay A, et al.: Real-world patient- and caregiver-reported outcomes in advanced breast cancer. Curr Oncol 25 (4): e282-e290, 2018.

- Van Houtven CH, Ramsey SD, Hornbrook MC, et al.: Economic burden for informal caregivers of lung and colorectal cancer patients. Oncologist 15 (8): 883-93, 2010.

- Siefert ML, Williams AL, Dowd MF, et al.: The caregiving experience in a racially diverse sample of cancer family caregivers. Cancer Nurs 31 (5): 399-407, 2008 Sep-Oct.

- Li C, Zeliadt SB, Hall IJ, et al.: Burden among partner caregivers of patients diagnosed with localized prostate cancer within 1 year after diagnosis: an economic perspective. Support Care Cancer 21 (12): 3461-9, 2013.

- Chen ML: The Growing Costs and Burden of Family Caregiving of Older Adults: A Review of Paid Sick Leave and Family Leave Policies. Gerontologist 56 (3): 391-6, 2016.

- Kim Y, Baker F, Spillers RL, et al.: Psychological adjustment of cancer caregivers with multiple roles. Psychooncology 15 (9): 795-804, 2006.

- Fenton ATHR, Keating NL, Ornstein KA, et al.: Comparing adult-child and spousal caregiver burden and potential contributors. Cancer 128 (10): 2015-2024, 2022.

- Ang WH, Lang SP, Ang E, et al.: Transition journey from hospital to home in patients with cancer and their caregivers: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer 24 (10): 4319-26, 2016.

- Rocío L, Rojas EA, González MC, et al.: Experiences of patient-family caregiver dyads in palliative care during hospital-to-home transition process. Int J Palliat Nurs 23 (7): 332-339, 2017.

- Geddie PI, Wochna Loerzel V, Norris AE: Family Caregiver Knowledge, Patient Illness Characteristics, and Unplanned Hospital Admissions in Older Adults With Cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 43 (4): 453-63, 2016.

- Tanco K, Prado B, Qian Y, et al.: A Comparison of Caregiver Burden of Patients with Advanced Cancer in Different Palliative Cancer Care Settings. J Palliat Med 24 (12): 1766-1775, 2021.

Coping Strategies and Self-Efficacy

As conceptualized, coping strategies mediate the relationship between positive or negative consequences and the perception that the demands of caregiving exceed the available resources. One group of investigators interviewed and surveyed 50 family caregivers of cancer patients receiving palliative care.[1] The aim was to describe the relationships between coping strategies and anxiety in caregivers. Anxiety was common in caregivers (76%). Emotion-based coping was associated with less anxiety, while dysfunctional coping was associated with increased anxiety. Perceived burden was also associated with increased anxiety.

As shown in the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, caregivers and patients are interconnected. Evidence demonstrates a link between patient coping style and caregiver adjustment. A cross-sectional study of baseline data from a trial of subspecialty palliative care confirmed the relationship in 275 family caregivers of patients with incurable lung or colorectal cancer.[2] The investigators demonstrated that caregivers experienced greater depressive symptoms when patients used emotional support coping or expressed optimism about their prognosis. Patient emotional support coping was associated with lower caregiver anxiety.

This interconnectedness between caregiver and patient also involves threat appraisal (the first step in the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping). A study of 484 dyads demonstrated that patient and caregiver symptom distress influenced their own, and in some cases each other's, cognitive appraisals.[3]

References:

- Perez-Ordóñez F, Frías-Osuna A, Romero-Rodríguez Y, et al.: Coping strategies and anxiety in caregivers of palliative cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 25 (4): 600-7, 2016.

- Nipp RD, El-Jawahri A, Fishbein JN, et al.: Factors associated with depression and anxiety symptoms in family caregivers of patients with incurable cancer. Ann Oncol 27 (8): 1607-12, 2016.

- Ellis KR, Janevic MR, Kershaw T, et al.: The influence of dyadic symptom distress on threat appraisals and self-efficacy in advanced cancer and caregiving. Support Care Cancer 25 (1): 185-194, 2017.

Assessment of Caregivers (Screening or Evaluation)

Caregiver assessment can be performed at any point of contact within the health care system. Ideally, a comprehensive caregiver assessment should be performed when the following occurs:[1]

- The patient is first diagnosed with cancer.

- The patient presents in the emergency department.

- A major transition is planned.

In systems where caregivers are assessed, practitioners can acknowledge caregivers as valued members of the health care team. Caregiver assessment can identify family members most at risk of developing physical and mental health difficulties, so that additional services can be planned accordingly.[1]

Multiple instruments to measure caregiver burden are available, including the Zarit Burden Interview,[2] among others.[3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10] Objective measures of caregiver burden comprise variables such as the number of hours spent providing care and an actual count of tasks the caregiver performs.[11][Level of evidence: II][12] Objective measures are usually short and easy to answer, often pointing to a clear direction for problem solving and direct intervention.[13] Caregiver assessment should reflect culturally competent practices.[14]

Although there are many tools for measuring caregiver burden, a review [15] found only eight tools in English for psychometric evaluation of cancer caregivers. Of the eight, the Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA) and Caregiver Quality of Life Index-Cancer (CQOLC) had the best psychometric performance. Additionally, 16 conceptual domains within five overarching themes were identified across the eight instruments. Although the tools showed overlap in several domains, there was no single tool that measured all. Therefore, in assessing caregiver burden, it is prudent to use two or more instruments to obtain an evaluation across all domains.

References:

- Feinberg LF: Caregiver assessment. Am J Nurs 108 (9 Suppl): 38-9, 2008.

- Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J: Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 20 (6): 649-55, 1980.

- Glajchen M, Kornblith A, Homel P, et al.: Development of a brief assessment scale for caregivers of the medically ill. J Pain Symptom Manage 29 (3): 245-54, 2005.

- Weitzner MA, Jacobsen PB, Wagner H, et al.: The Caregiver Quality of Life Index-Cancer (CQOLC) scale: development and validation of an instrument to measure quality of life of the family caregiver of patients with cancer. Qual Life Res 8 (1-2): 55-63, 1999.

- Weitzner MA, McMillan SC: The Caregiver Quality of Life Index-Cancer (CQOLC) Scale: revalidation in a home hospice setting. J Palliat Care 15 (2): 13-20, 1999.

- Given CW, Given B, Stommel M, et al.: The caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Res Nurs Health 15 (4): 271-83, 1992.

- Robinson BC: Validation of a Caregiver Strain Index. J Gerontol 38 (3): 344-8, 1983.

- Minaya P, Baumstarck K, Berbis J, et al.: The CareGiver Oncology Quality of Life questionnaire (CarGOQoL): development and validation of an instrument to measure the quality of life of the caregivers of patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer 48 (6): 904-11, 2012.

- Wells DK, James K, Stewart JL, et al.: The care of my child with cancer: a new instrument to measure caregiving demand in parents of children with cancer. J Pediatr Nurs 17 (3): 201-10, 2002.

- Zaleta AK, Miller MF, Fortune EE, et al.: CancerSupportSourceTM -Caregiver: Development of a distress screening measure for cancer caregivers. Psychooncology 32 (3): 418-428, 2023.

- Bookwala J, Schulz R: A comparison of primary stressors, secondary stressors, and depressive symptoms between elderly caregiving husbands and wives: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. Psychol Aging 15 (4): 607-16, 2000.

- Gaugler JE, Hanna N, Linder J, et al.: Cancer caregiving and subjective stress: a multi-site, multi-dimensional analysis. Psychooncology 14 (9): 771-85, 2005.

- Honea NJ, Brintnall R, Given B, et al.: Putting Evidence into Practice: nursing assessment and interventions to reduce family caregiver strain and burden. Clin J Oncol Nurs 12 (3): 507-16, 2008.

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S: Ethnic differences in stressors, resources, and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: a meta-analysis. Gerontologist 45 (1): 90-106, 2005.

- Shilling V, Matthews L, Jenkins V, et al.: Patient-reported outcome measures for cancer caregivers: a systematic review. Qual Life Res 25 (8): 1859-76, 2016.

The Needs of Caregivers During Specific Phases of the Cancer Trajectory

The cancer experience may be conceptualized as occurring in several relatively distinct phases, from screening to diagnosis and treatment to either long-term survivorship or the end of life.[1] The phases differ in likely activities, goals, and likely outcomes for the patient. It seems reasonable to assume that the experiences of the caregiver also vary, given the interdependence of caregiver and patient.

Studies Comparing Caregivers at Different Points in the Cancer Trajectory

Few studies directly compare caregivers of cancer patients across the disease trajectory or patients at different stages of disease. One research group conducted a qualitative study and interviewed 15 cancer caregivers before, during, and at 4 months after bone marrow transplant. Although the exemplars varied across the trajectory, two consistent themes regarding caregiver concerns emerged: uncertainty and the need for more information.[2]

Another study compared the results of two cross-sectional studies of caregivers of cancer patients who were in the late palliative phase or who were attending a pain clinic (which the authors termed the curative phase).[3] The authors found no differences in the mean scores of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) or the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) as measures of quality of life (QOL). The results should be interpreted with caution, given the different inclusion criteria and different time periods of the study. Furthermore, the group means may obscure meaningful changes in individual caregivers over time.

A separate analysis demonstrated that symptom burdens in patients did not vary between cohorts, but both groups scored high on measures of weakness and fatigue.[4] Caregivers reported higher rates of depression when patients had insomnia, but the association did not vary between cohorts. However, the methodology of the studies limits the drawing of firm conclusions.

In a cross-sectional study of 1,580 caregivers of patients with heterogenous cancer types, caregivers of patients undergoing active treatment had a significantly lower mean score on the Distress Thermometer than caregivers of patients in follow-up.[5][Level of evidence: II] Mean scores on another measure of caregiver distress, the Caregiver Risk Screen, were not significantly different across groups. Conversely, caregivers of patients undergoing active treatment reported significantly worse QOL on the Caregiver Quality of Life Index–Cancer than caregivers of patients in follow-up. One possible explanation for these findings is that while patients' physical and practical needs may decrease after treatment, caregivers may experience heightened uncertainty and fear of cancer recurrence during survivorship.[6,7]

Survivorship

The evidence demonstrates that although the prevalence of unmet needs diminishes over time, a significant minority of caregivers continues to experience needs related to the cancer experience during the survivorship phase.

For example, a longitudinal study was designed to track the psychosocial, financial, and occupational impact of having ongoing needs as a caregiver in Australia.[8] The investigators analyzed responses to the Supportive Care Needs Survey—Partners and Caregivers (SCNS–P&C) from 547 caregivers at 6 months, 519 caregivers at 12 months, and 443 caregivers at 24 months after the cancer diagnosis. Of note, 444 of the original 547 participants completed surveys at 12 months, and 372 completed surveys at 24 months.

Several findings deserve emphasis:

- The proportion of caregivers reporting any unmet need decreased from 50.2% at 6 months to 30.7% at 24 months.

- A similar decline was seen for caregivers who reported at least five or ten unmet needs, although the baseline prevalence was lower.

- The most pressing unmet needs were related to concerns about recurrence, reducing stress in the survivor's life, and understanding the survivor's experience.

- Unmet needs were negatively associated with caregivers' well-being (although not uniformly).

In a longitudinal study of 120 dyads of patients with hepatobiliary or pancreatic cancer and their caregivers, 25% of caregivers reported high levels of chronic depressive symptoms, and 21% had high levels of stress at diagnosis.[9][Level of evidence: II] Caregivers with high depressive symptoms and stress at diagnosis remained at high levels up to 18 months postdiagnosis, whereas those with low to moderate depressive symptoms and stress at diagnosis declined over time. Patient depressive symptoms also predicted caregiver stress. These findings suggest that caregivers with higher levels of depressive symptoms and stress at diagnosis may be the most vulnerable over time, but further research is needed in more diverse samples, as most caregivers were women (85%). Similarly, a 2021 study found that in 111 caregivers of newly diagnosed cancer patients, poorer caregiver QOL was associated with higher levels of caregiver depression, anxiety, and stress, and that caregiver QOL and levels of social support changed over the treatment trajectory.[10][Level of evidence: II]

The End of Life

The end-of-life experiences of patients with advanced cancer influence the burden on caregivers and their eventual psychological adjustment during bereavement. A longitudinal study of caregivers of women with advanced-stage ovarian cancer provides valuable insights into the caregiver's experience in the last year of the patient's life.[11] Ninety-nine caregivers completed measures every 3 months for 2 years. The caregivers reported lower-than-expected mental and physical QOL. The average distress and number of unmet needs increased over time. Perceived social support did not change. Caregiver distress was predicted by lower optimism, higher unmet needs, and shortened time to patient death. Patient QOL was not a predictor. In the last 6 months of the patient's life, managing emotions about poor prognosis and balancing work with caregiving demands were related to high unmet needs in the caregiver.

One potential source of caregiver distress toward the end of life is the ambiguity around caregivers' role in decisions to limit potentially life-sustaining treatments such as chemotherapy or resuscitation. Two studies provide clarifying observations.[12,13] One study embedded researchers during hospitalizations of patients with advanced cancer to record the participation of caregivers in decisions to limit treatment.[12] The investigators identified 70 patients, but only 63 had caregivers present. In the cohort, only 32% of relatives were involved, both positively and negatively. Clinicians were more often aware of patients' preferences when relatives were present (78% vs. 29%, P = .014). Caregivers, however, were not always in agreement and, in one-third of the observations, contradicted the patients. Thus, caregivers may be a source of insight but do not necessarily accurately reflect patients' wishes.

The caregiver's importance to the decision process may vary based on clinicians' attitudes. In an interview study of oncology physicians and nurses, two broad perspectives were found: maintaining patient autonomy independent of caregiver influence and facilitating decision-making by actively involving caregivers seeking consensus.[13] These perspectives were based on a desire to enhance the positive aspects of caregivers' support (e.g., emotional, encouragement to plan, and understanding of information) while minimizing the potential barriers (e.g., family reluctance to accept the patient is at the end of life, the need to mediate conflicts, and the increased time required to include caregivers). These findings highlight the potential value of caregivers and the need to develop specific strategies.

Hospice care can provide critical support to caregivers as well as to patients. One group of investigators compared the burden and QOL of caregivers of patients with advanced cancer who were receiving active treatment with the burden and QOL of caregivers of patients who were receiving hospice care.[14] The goal was to characterize the demands unique to the hospice phase of care. The investigators found no difference in the perceived burden of caregiving and increased role limitations due to mental or emotional challenges; however, caregivers in the hospice group reported fewer physical limitations. Similarly, another group reported that longer hospice stays were associated with better patient QOL and better caregiver adjustment during bereavement.[15]

One potential explanation for the benefit of hospice is that caregivers are reassured by the higher quality of end-of-life care and the honoring of patients' goals. One study analyzed interviews with 1,146 family members of Medicare beneficiaries who died from advanced-stage lung or colorectal cancer.[16] The results demonstrated that hospice enrollment was associated with more "excellent" ratings for quality of care reported by family members. Similarly, patients who received intensive care or had short enrollments were less frequently reported to have died in their preferred place.[17] For more information, see Hospice.

Caregivers may also require support to effectively participate in decisions about whether to provide patients with artificial nutrition or hydration (ANH). Investigators conducted a prospective cross-sectional survey of 39 patients with advanced cancer and 30 relatives about their views on ANH.[18] Only 24% of relatives stated they would opt out of ANH if deciding on behalf of their loved ones; 48% were against hydration. Patients were less concerned with adverse physical symptoms such as pain, agitation, and hunger than were their relatives. Patients endorsed their family members' opinions as being important in the decisions. For more information, see the Artificial Hydration section in Last Days of Life.

References:

- Levit LA, Balogh EP, Nass SJ, et al., eds.: Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. The National Academies Press, 2013. Also available online. Last accessed March 11, 2024.

- Von Ah D, Spath M, Nielsen A, et al.: The Caregiver's Role Across the Bone Marrow Transplantation Trajectory. Cancer Nurs 39 (1): E12-9, 2016 Jan-Feb.

- Grov EK, Valeberg BT: Does the cancer patient's disease stage matter? A comparative study of caregivers' mental health and health related quality of life. Palliat Support Care 10 (3): 189-96, 2012.

- Valeberg BT, Grov EK: Symptoms in the cancer patient: of importance for their caregivers' quality of life and mental health? Eur J Oncol Nurs 17 (1): 46-51, 2013.

- Decadt I, Laenen A, Celus J, et al.: Caregiver distress and quality of life in primary caregivers of oncology patients in active treatment and follow-up. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 30 (3): e13399, 2021.

- Shilling V, Starkings R, Jenkins V, et al.: The pervasive nature of uncertainty-a qualitative study of patients with advanced cancer and their informal caregivers. J Cancer Surviv 11 (5): 590-603, 2017.

- Balfe M, O'Brien K, Timmons A, et al.: The unmet supportive care needs of long-term head and neck cancer caregivers in the extended survivorship period. J Clin Nurs 25 (11-12): 1576-86, 2016.

- Girgis A, Lambert SD, McElduff P, et al.: Some things change, some things stay the same: a longitudinal analysis of cancer caregivers' unmet supportive care needs. Psychooncology 22 (7): 1557-64, 2013.

- Chen Q, Terhorst L, Geller DA, et al.: Trajectories and predictors of stress and depressive symptoms in spousal and intimate partner cancer caregivers. J Psychosoc Oncol 38 (5): 527-542, 2020 Sep-Oct.

- Peh CX, Liu J, Mahendran R: Quality of life and emotional distress among caregivers of patients newly diagnosed with cancer: Understanding trajectories across the first year post-diagnosis. J Psychosoc Oncol 38 (5): 557-572, 2020 Sep-Oct.

- Butow PN, Price MA, Bell ML, et al.: Caring for women with ovarian cancer in the last year of life: a longitudinal study of caregiver quality of life, distress and unmet needs. Gynecol Oncol 132 (3): 690-7, 2014.

- Hauke D, Reiter-Theil S, Hoster E, et al.: The role of relatives in decisions concerning life-prolonging treatment in patients with end-stage malignant disorders: informants, advocates or surrogate decision-makers? Ann Oncol 22 (12): 2667-2674, 2011.

- Laryionava K, Hauke D, Heußner P, et al.: "Often Relatives are the Key […]" -Family Involvement in Treatment Decision Making in Patients with Advanced Cancer Near the End of Life. Oncologist 26 (5): e831-e837, 2021.

- Spatuzzi R, Giulietti MV, Ricciuti M, et al.: Quality of life and burden in family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer in active treatment settings and hospice care: A comparative study. Death Stud 41 (5): 276-283, 2017 May-Jun.

- Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al.: Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 300 (14): 1665-73, 2008.

- Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al.: Family Perspectives on Aggressive Cancer Care Near the End of Life. JAMA 315 (3): 284-92, 2016.

- Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, et al.: Place of death: correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers' mental health. J Clin Oncol 28 (29): 4457-64, 2010.

- Bükki J, Unterpaul T, Nübling G, et al.: Decision making at the end of life--cancer patients' and their caregivers' views on artificial nutrition and hydration. Support Care Cancer 22 (12): 3287-99, 2014.

Interventions to Prevent, Reduce, or Ameliorate Caregiver Burden

Many types of interventions have been tested to address the needs of informal caregivers.[1,2,3] The interventions have focused on improving outcomes for the individual patient, caregiver, or patient-caregiver dyad.[1] The types of interventions studied and the goals of each intervention are summarized below.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT): To use psychoeducational and social interventions to reduce caregiver perceived burden and/or feelings of distress.

- Complementary and/or alternative medicine therapies: To reduce caregiver distress/burden through guided imagery, reflexology, reminiscence therapy, massage therapy, and/or healing touch.

- Family/couples therapy: To improve the functioning of the couple and/or family unit.

- Interpersonal therapy: To provide individualized counseling to reduce the psychological consequences of caregiving burdens.

- Problem solving/skill building: To develop caregiving skills, including the ability to assess and manage patients' symptoms, identify solutions to caregiving problems, and enhance caregivers' ability to cope with cancer caregiving roles and responsibilities.

- Psychoeducational: To address the information needs of cancer caregivers, including information related to diagnosis, prognosis, coping, self-care/home care, impact on partners/family, and hospital care or follow-up/rehabilitation.[4]

- Subspecialty palliative care: To directly address caregivers' concerns and improve outcomes by improving patient outcomes.

- Supportive therapy: To address the emotional needs of informal caregivers.

The efficacy of these interventions has been mixed. Findings from a few meta-analyses have identified positive effects (small to medium effects) of psychosocial-educational interventions on caregivers and on patient-caregiver outcomes.[5,6,7] However, many studies are limited by small sample sizes and short assessments, and they often vary in outcomes depending on the study focus (patient vs. caregiver vs. patient-caregiver dyads).[1]

Meta-analyses

One meta-analysis of 29 randomized clinical trials published from 1983 to 2009 [6] identified the following three major types of interventions:

- Psychoeducational.

- Skill building/problem solving.

- Therapeutic counseling.

The authors used a conceptual framework to organize the outcome data, integrating stress and coping theory, CBT, and quality of life (QOL) frameworks. Overall, all three interventions showed promise (small to moderate effect) for improving the following outcomes:

- Caregiver burden (11 studies; overall effect size, Hedge's g [g] = 0.22).

- Caregivers' ability to cope (10 studies; overall effect size, g = 0.47 within the first 3 months, which remained significant 3 to 6 months later [overall effect size, g = 0.20] and 6 months later [g = 0.35]).

- Self-efficacy (8 studies; overall effect size, g = 0.25, which remained significant at 3 to 6 months' follow-up [g = 0.20] and beyond).

- Aspects of QOL, including physical functioning (7 studies; g = 0.22 at 3 to 6 months' follow-up and g = 0.26 at 6 months' follow-up), distress and anxiety (16 studies; g = 0.20 during the first 3 months), and marital/family relationships (10 studies; g = 0.20); there was no significant improvement in depression or social functioning.

A follow-up systematic review of the literature identified 49 intervention studies that addressed caregiver demands/burden.[3] Eight different types of interventions were noted, with most studies categorized as psychoeducational, problem solving, supportive therapy, and family/couples therapy. The authors noted only three studies that used CBT. However, all three studies using CBT noted significant improvement in psychological functioning in informal caregivers. Overall, the authors suggested that programs that were structured, integrative, and goal oriented appeared to offer the greatest benefits.[3]

This initial work was expanded upon with a synthesis and meta-analyses of the effectiveness of CBT for improving psychological functioning in informal caregivers.[2] The authors identified a small statistical effect of CBT (g = 0.08); however, this significant effect disappeared when randomized controlled trials were reviewed alone. The authors suggested that the broad definition of CBT and variations in the definition of informal caregivers may have limited results.[2]

Two additional reviews focused on literature published up until 2016.[8,9] One group of investigators conducted a systematic review of 21 psychosocial interventions for improving QOL, depression, and anxiety in cancer caregivers.[8] This report and others have illustrated some noteworthy interventions that have been used in multiple studies.

- Psychoeducational intervention: The FOCUS Program is an informational and support program that includes five core content areas: F amily involvement, O ptimistic attitude, C oping effectiveness, U ncertainty reduction, and S ymptom management. This intervention has been tested in multiple randomized controlled trials and has shown improvement in caregiver QOL.[10,11]

- Problem-solving intervention: COPE (C reativity, O ptimism, P lanning, E xpert Information) is a problem-solving model that has been used by multiple investigators and has shown improvement in caregiver QOL,[12,13] burden of patient symptoms, and caregiving task burden.[12] This program has also been used in combination with other cognitive behavioral trials with some success.[14]

- Psychoeducational and supportive therapy: CHESS (C omprehensive H ealth E nhancement S upport S ystem) is a Web-based lung cancer information, communication, and coaching system for caregivers.[15] This program was tested in 285 informal caregivers of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Caregivers were randomly assigned to a comparison group that received standard care plus a laptop computer with Internet access (if needed) and a list of lung cancer and palliative care websites; or to a treatment group that received standard care plus a laptop computer and Internet access (if needed) and access to the CHESS lung cancer website, "Coping with Lung Cancer: A Network of Support." Caregivers assigned to CHESS had significant small to moderate effects in improved caregiver burden and negative mood. This is a good example of using the Web to reach informal caregivers, who are often unable to attend supportive training programs in person.

Individual Studies

This section provides information about a few individual landmark studies.

Overview of study limitations and unresolved questions

A number of limitations in studies to date prevent any conclusions about choosing an optimal intervention. Salient limitations include the following:

- The variation in intervention delivery across studies, from in-person sessions to telephone, online, or Web-based applications.

- The lack of consensus regarding the definition of informal caregivers and types of interventions, making comparisons across studies difficult.

- The potential lack of scalability of interventions studied in a limited number of sites, leaving the unanswered question of how to provide interventions to rural populations and/or those with transportation concerns.

- The frequent lack of a match between the primary outcome measure and the target of the intervention. For example, interventions focused on problem solving often failed to assess improvement in the capacity to solve problems, but instead measured more distal outcomes such as psychological adjustment—therefore raising questions about attributing intervention effects.

- The unrecognized variations in the levels of caregiver burden or distress among study participants. Researchers noted that informal caregivers who were most distressed were more likely to self-select out of a trial; or, if enrolled, they often failed to complete the intervention, which affected the evaluation. In addition, the investigators have suggested that efficacy has varied because of low baseline levels of caregiver burden/distress or inadequate follow-up that has resulted in the inability to identify changes in levels of distress.

Limitations will be addressed as future studies, as follows:

- Use consensus definitions for informal caregivers and interventional categories.[2]

- Identify the more-vulnerable caregiving populations (e.g., socially isolated caregivers, rural residents, older people, members of lower socioeconomic groups, and people with the most complicated care/needs).[1]

- Incorporate risk stratification to target highly stressed informal caregivers and patients.[1] Future studies may need to focus on those most in need to adequately demonstrate intervention effectiveness.

- Incorporate technology not only to improve interventions but also to improve access to interventional support.[1]

Overview of results of selected studies

The following two tables contain brief descriptions of noteworthy reports to aid in understanding potential interventions and benefits. Table 1 organizes studies by type of intervention and highlights positive and negative studies. As outlined in the previous section, however, methodological limitations prevent comparisons or conclusions.[1]

| Intervention Type | Positive Results | Negative Results |

|---|---|---|

| IC = informal caregiver; N/A = not applicable; QOL = quality of life. | ||

| Psychoeducation | Improved knowledge and/or ability to provide care[16,17,18,19,20,21,22] | Unimproved mood (anxiety and distress)[23] |

| Improved psychological functioning (depression, anxiety, stress) and reduced caregiver burden[15,24,25,26,27] | No significant improvement in caregiver burden[28] | |

| Improved patient-reported functional support and marital satisfaction[24] | Unimproved QOL[29] | |

| Improved coping and mental health, decreased depressive symptoms, and lower risk of maladaptive coping[30] | N/A | |

| Problem solving/skill building | Improved problem solving[31,32,33,34,35,36] | No decrease in IC depressive symptoms[37,38] |

| Improved IC confidence,[32]self-efficacy[36,37,39] | No improvement in IC coping or help seeking[40] | |

| Improved psychological functioning (decreased IC depressive symptoms,[33]anxiety,[35]distress,[36]and negative affect[34]) | ||

| Decreased patient depressive symptoms[33] | ||

| Improved health outcomes (fatigue)[36] | ||

| Improved QOL[35] | ||

| Supportive therapy | Improved IC perception of support/knowledge[41] | No significant improvement in IC psychological functioning (depression, anxiety)[37,42] |

| Unimproved IC QOL[37,43] | ||

| Family/couples therapy | Improved marital functioning/relationships[44,45] | Unimproved state anxiety or traumatic stress or distress[46] |

| Less IC-reported negative appraisals of caregiving[10,47] | ||

| Improved communication skills[47] | ||

| Improved psychological functioning (distress, depression, anxiety in ICs, patients)[45,48,49] | ||

| Improved QOL[11,50] | ||

| Cognitive behavioral therapy | Improved psychological functioning (reductions in distress, depressive symptoms)[51,52,53] | N/A |

| Decreased burden of cancer symptoms[12] | ||

| Improved self-efficacy[54] | ||

| Improved QOL[12] | ||

| Interpersonal therapy | Improved psychological function (decreased depression, anxiety)[55,56] | N/A |

| Improved QOL[56,57] | ||

| Integrative, alternative, and complementary therapy | Massage: improvements in IC depression, anxiety, fatigue[58] | N/A |

| Strength training: improvements in mental health but approaching statistical significance (0.06)[59] | ||

| Mindfulness-based stress reduction: | ||

| – Reduced caregiver burden, yet no significant reduction in psychological distress for patients and partners[60] | ||

| – Significant improvement in patient psychological functioning (decreased stress, anxiety) and reduction but no statistical improvement in IC psychological functioning and QOL[61] | ||

Table 2 highlights some of the investigational studies that support the effectiveness of psychoeducational, problem-solving, and CBT interventions in which most of the work has been conducted. In addition, the table displays the outcomes (resources and/or coping) that were improved in each of these studies.

| Intervention Type/References | Outcomes: Improved Resources and/or Coping | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QOL = quality of life. | ||||||

| Psychoeducation | Knowledge of care/role | Problem solving | Self-efficacy | Psychological functioning | Symptoms | QOL |

| – Ferrell et al., 1995[16] | X | |||||

| – Horowitz et al., 1996[25] | X | X | ||||

| – DuBenske et al., 2014[15] | X | |||||

| – Northouse et al., 2013[11] | X | X | ||||

| – Northouse et al., 2014[50] | X | X | X | |||

| – Badr et al., 2015[26] | X | |||||

| Problem solving | Knowledge of care/role | Problem solving | Self-efficacy | Psychological functioning | Symptoms | QOL |

| – Sahler et al., 2002[34] | X | X | X | |||

| – Nezu et al., 2003[33] | X | X | X | |||

| – Cameron et al., 2004[32] | X | X | X | |||

| – Bevans et al., 2010[31] | X | X | ||||

| – Demiris et al., 2012[35] | X | X | X | |||

| – Bevans et al., 2014[36] | X | X | X | X | ||

| Cognitive behavioral therapy | Knowledge of care/role | Problem solving | Self-efficacy | Psychological functioning | Symptoms | QOL |

| – Keefe et al., 2005[54] | X | |||||

| – Carter, 2006[51] | X | |||||

| – Cohen et al., 2006[52] | X | |||||

| – Given et al., 2006[53] | X | X | ||||

| – McMillan et al., 2006[12] | X | X | ||||

References:

- Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, et al.: Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer 122 (13): 1987-95, 2016.

- O'Toole MS, Zachariae R, Renna ME, et al.: Cognitive behavioral therapies for informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology 26 (4): 428-437, 2017.

- Applebaum AJ, Breitbart W: Care for the cancer caregiver: a systematic review. Palliat Support Care 11 (3): 231-52, 2013.

- Adams E, Boulton M, Watson E: The information needs of partners and family members of cancer patients: a systematic literature review. Patient Educ Couns 77 (2): 179-86, 2009.

- Badr H, Krebs P: A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for couples coping with cancer. Psychooncology 22 (8): 1688-704, 2013.

- Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, et al.: Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin 60 (5): 317-39, 2010 Sep-Oct.

- Griffin JM, Meis LA, MacDonald R, et al.: Effectiveness of family and caregiver interventions on patient outcomes in adults with cancer: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 29 (9): 1274-82, 2014.

- Fu F, Zhao H, Tong F, et al.: A Systematic Review of Psychosocial Interventions to Cancer Caregivers. Front Psychol 8: 834, 2017.

- Frambes D, Given B, Lehto R, et al.: Informal Caregivers of Cancer Patients: Review of Interventions, Care Activities, and Outcomes. West J Nurs Res 40 (7): 1069-1097, 2018.

- Northouse L, Kershaw T, Mood D, et al.: Effects of a family intervention on the quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family caregivers. Psychooncology 14 (6): 478-91, 2005.

- Northouse LL, Mood DW, Schafenacker A, et al.: Randomized clinical trial of a brief and extensive dyadic intervention for advanced cancer patients and their family caregivers. Psychooncology 22 (3): 555-63, 2013.

- McMillan SC, Small BJ, Weitzner M, et al.: Impact of coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer: a randomized clinical trial. Cancer 106 (1): 214-22, 2006.

- Meyers FJ, Carducci M, Loscalzo MJ, et al.: Effects of a problem-solving intervention (COPE) on quality of life for patients with advanced cancer on clinical trials and their caregivers: simultaneous care educational intervention (SCEI): linking palliation and clinical trials. J Palliat Med 14 (4): 465-73, 2011.